The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a nonpartisan agency of Congress, made official projections of the Affordable Care Act’s impact on insurance coverage rates and the costs of providing subsidies to consumers purchasing health plans in the insurance marketplaces. This analysis finds that the CBO overestimated marketplace enrollment by 30 percent and marketplace costs by 28 percent, while it underestimated Medicaid enrollment by about 14 percent. Nonetheless, the CBO’s projections were closer to realized experience than were those of many other prominent forecasters. Moreover, had the CBO correctly anticipated income levels and health care prices in 2014, its estimate of marketplace enrollment would have been within 18 percent of actual experience. Given the likelihood of additional reforms to national health policy in future years, it is reassuring that, despite the many unforeseen factors surrounding the law’s rollout and participation in its reforms, the CBO’s forecast was reasonably accurate.

Forecasts of the impacts of health care legislation under consideration, particularly those conducted by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO), are a critical element of the policymaking process. This makes their accuracy vitally important. In practice, however, the complexity of policies and their changes over time make it extremely difficult to assess the accuracy of the forecasts or the underlying models they rely upon. The passage and implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which created new pathways to health insurance coverage, provides an exceptional opportunity to conduct such an assessment.

The accuracy of forecasts of the effects of new legislation depends on two key elements. First, because there is generally a lag between enactment of a policy and its implementation, accuracy depends on how well the forecasting entity predicts the conditions—particularly income levels and health care costs—at the time of implementation. Second, accuracy depends on how well the model assumptions and parameters predict the effects of the legislation itself.

In this brief, we examine the accuracy of the CBO’s March 2010 estimates of the effects of the ACA’s health insurance marketplaces and of its July 2012 estimates of the Medicaid coverage provisions in the year 2014 on: 1) the number of insured through the marketplaces and Medicaid and 2) spending on marketplace subsidies. We also compare the CBO estimates with those made by four other forecasters—the Office of the Actuary of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the RAND Corporation, the Urban Institute; and the Lewin Group. (See Appendix A for a comparison of these five forecasting models.) Assessing the accuracy of these forecasts is simplified by the fact that no significant health reform legislation passed between enactment of the ACA in 2010 and implementation of the coverage expansions in 2014. The Supreme Court’s decision in NFIB v. Sebelius in 2012 making Medicaid expansion optional, however, led many states to reject Medicaid expansion. In the wake of that decision, the CBO revised its forecasts of ACA costs and coverage. 1 We make adjustments to Medicaid estimates from all modelers to reflect what their models were likely to forecast for 2014 under post–Supreme Court rules, using the CBO’s July 2012 revised estimates.

How We Evaluated the Accuracy of ACA Forecasting Models

To assess the accuracy of predictions of marketplace coverage, we examined both total and subsidized marketplace enrollment, focusing on the latter. 2 To assess the accuracy of predictions of marketplace costs, we examined: 1) estimates of premiums for the second-lowest silver plan premium, which is the “benchmark” for determining subsidies; 2) the average subsidy across the entire population of marketplace enrollees (including both premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions) per enrollee; 3) the average subsidy per subsidized enrollee; 4) total outlays for premium tax credits; and 5) total outlays for cost-sharing reductions.

For Medicaid coverage, we focused on new Medicaid enrollment only, as we cannot separate the actual costs of the Medicaid expansion population from those of the continuing Medicaid population. In comparing estimates of marketplace enrollment and costs and Medicaid enrollment across models, we adjusted the Lewin and Urban Institute enrollment estimates, which were made based on the assumption that the law was fully implemented in 2010, to construct estimates for 2014, using the CBO’s phase-in assumptions. In addition, we further adjusted Urban’s premium and subsidy estimates to 2014 using assumptions about cost inflation.

To distinguish the contributions of the effects of changes in baseline conditions from those of the CBO model’s parameters, we simulate how the CBO’s model might have forecast enrollment had the agency known the actual income levels and health insurance premiums in 2014.

Health insurance expansions under the ACA occur through the marketplaces, where eligible individuals can obtain coverage subsidized through tax credits, and through expansions of Medicaid eligibility. All the modelers considered here treat these two paths to coverage differently.

Health insurance subsidies in the marketplace are designed to ensure that health plan premiums and out-of-pocket costs are affordable. The amount of a subsidy is determined by applicants’ income. For example, for those in households earning between 300 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level in 2014, monthly health plan costs for the benchmark plan (the second-lowest silver plan sold in a marketplace) were to be no more than 9.5 percent of income. If they were greater, the subsidy would have paid the difference. To predict take-up of subsidized coverage, all of the models consider how people might react to the difference between the pre-subsidy and post-subsidy prices. Increases in health insurance premiums make more people eligible for subsidies (because the price of the benchmark plan exceeds the specified percentage of income for more people) and raise the participation rate among those eligible, because the subsidy is larger relative to the pre-subsidy price. Variation among models in predicted marketplace participation may differ because of differences in assumptions about: the baseline conditions (i.e., premium levels before the ACA, income levels, and number of uninsured); future conditions (e.g., benchmark plan premiums); or model parameters (e.g., related to price responsiveness).

Modelers forecast Medicaid enrollment by assuming that a fixed share of those who are eligible will take up coverage. The variation among models in predicted Medicaid enrollment levels may be the result of differences in estimates of the size of the Medicaid-eligible population or because of differences in these assumed take-up rates.

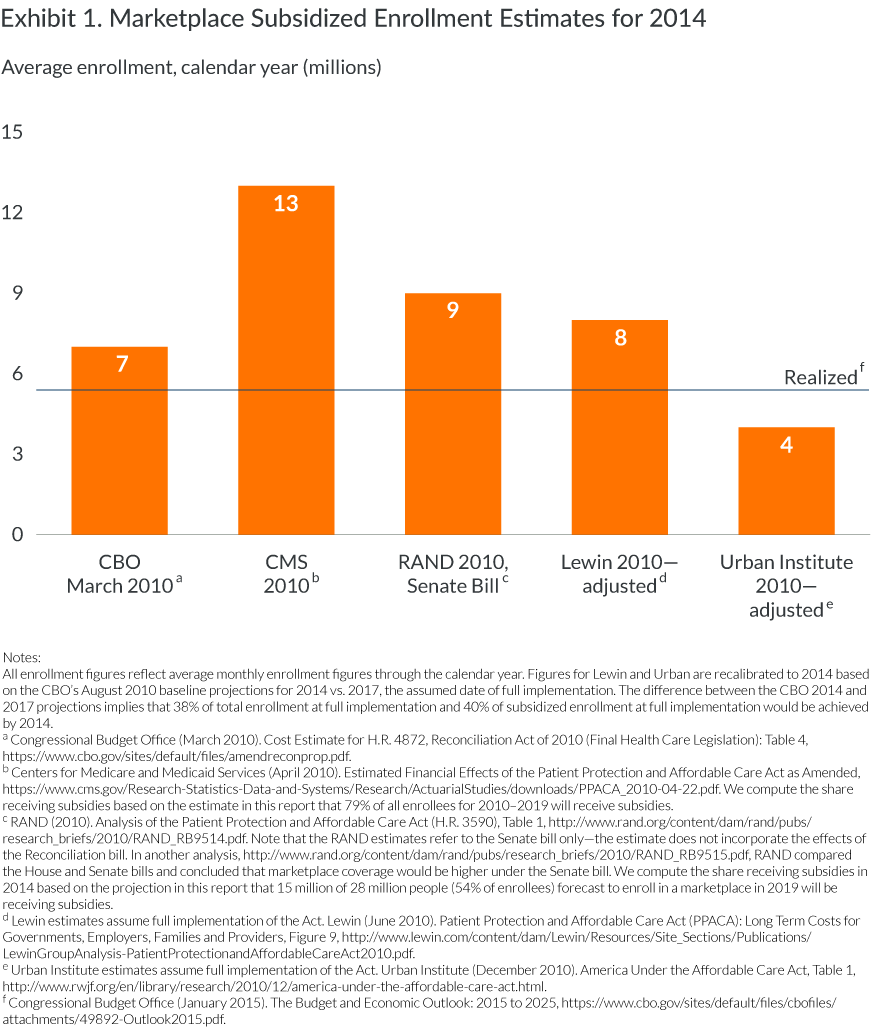

In 2010 CBO projected that average marketplace enrollment over the 2014 calendar year would be 8 million, with 7 million receiving subsidies (Exhibit 1). Other modelers generally anticipated higher participation. CMS projected enrollment at 17 million, with 13 million receiving subsidies, 3 while RAND forecast 16 million, with 9 million receiving subsidies. 4 Estimates from the Lewin Group 5 and the Urban Institute, 6 adjusted for phase-in using the CBO assumptions, projected 10 million and 9 million enrollees, with 8 million and 4 million receiving subsidies, respectively.

Actual enrollment in the marketplaces was lower than any of these forecasts, in part because it ramped up relatively slowly, with a surge at the end. While total enrollment reached 8 million by the end of the open-enrollment period, only about 6 million, 7 on average, were covered through the marketplaces over the course of the calendar year. About 5 million people, 8 87 percent of those enrolled in marketplaces, received subsidies.

The CBO’s original projection in 2010 was that 10 million people would enroll in the Medicaid expansion in 2014. The agency reduced this figure by about 30 percent, to 7 million, after the Supreme Court ruling (Exhibit 2). We adjusted projections made by CMS, the Urban Institute, Lewin, and RAND, all made prior to the Supreme Court ruling, using the ratio between the CBO’s 2010 and 2012 estimates. After adjustment, the CMS projection suggests that, in 2014, 16 million people would enroll in Medicaid, while the RAND projection suggests that just 3 million would do so. After adjustments for the law’s implementation in 2014 (rather than 2010) and the Supreme Court ruling, the Lewin and Urban forecasts for Medicaid enrollment were 6 and 7 million, respectively. The actual increase in Medicaid enrollment because of the ACA was about 8 million on average through 2014.

(average enrollment calendar year in millions)

| Source and date of projection | CMS 2010—adjusted a | RAND 2010, Senate Bill—adjusted b | Lewin 2010—adjusted c | Urban Institute 2010—adjusted d | CBO July 2012 e | Realized 2014 f |

| Medicaid enrollment | 16 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| Medicaid take-up g | 95% | 82% | 74% | 57% | 55%–70% | |

| Uninsured change | –20 | –6 | –14 | –13 | –14 | –12 |

| Uninsured total | 32 | 59 | 37 | 43 | 41 | 42 |

Notes: Figures for Lewin and Urban are recalibrated to 2014 based on the CBO’s August 2010 baseline projections for 2014 vs. 2017, the assumed date of full implementation. The difference between the CBO 2014 and 2017 projections implies that 38% of total enrollment at full implementation, 40% of subsidized enrollment at full implementation, and 18% of unsubsidized enrollment at full implementation would be achieved by 2014.

All figures from CMS, RAND, Lewin, and Urban are adjusted based on the CBO’s estimate of the effect of the Supreme Court decision on Medicaid enrollment and uninsurance rates. The CBO estimated that because of the Supreme Court decision, Medicaid enrollment would be 70% as high as initially predicted, the decline in the number uninsured would be about three-quarters as high as initially predicted, and the remaining number of uninsured would be about one-third higher than initially predicted.

a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (April 2010), Estimated Financial Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act as Amended: Table 2, http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/downloads/PPACA_2010-04-22.pdf.

b RAND (2010). Analysis of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (H.R. 3590): Table 1, http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_briefs/2010/RAND_RB9514.pdf.

c Lewin estimates assume full implementation of the Act. Lewin (June 2010). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA): Long Term Costs for Governments, Employers, Families and Providers: Figure 9, http://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/LewinGroupAnalysis-PatientProtectionandAffordableCareAct2010.pdf.

d Urban Institute estimates assume full implementation of the Act. Urban Institute, (December 2010). America Under the Affordable Care Act: Table 1, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412267-America-Under-the-Affordable-Care-Act.PDF.

e Congressional Budget Office (July 2012). Estimates for the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act Updated for the Recent Supreme Court Decision: Table 3, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43472-07-24-2012-CoverageEstimates.pdf.

f Congressional Budget Office (January 2015). The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2015 to 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/49892-Outlook2015.pdf.

g Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (March, 2012). Understanding Participation Rates in Medicaid: Implications for The Affordable Care Act, http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2012/medicaidtakeup/ib.shtml. Take-up rates estimated based on CPS estimate of number of citizens not enrolled in Medicaid or Medicare, ages 0–64, with incomes

The effect of the ACA on the number of uninsured depends on the expected baseline number of uninsured people and the number who enroll in the marketplaces and in Medicaid. In its March 2010 projection, the CBO projected that the ACA would reduce the number of uninsured in 2014 by 19 million, from the nearly 51 million otherwise anticipated to 31 million. 9 In its revised projection after the Supreme Court decision making Medicaid expansion optional, the CBO assumed a higher baseline number of uninsured (nearly 56 million) and a smaller reduction in the number of uninsured of 14 million, leaving 41 million uninsured (Exhibit 2). After adjustment for the Supreme Court effect, CMS projected a much larger reduction in the uninsured population (20 million) and a lower number of remaining uninsured (32 million). Lewin and Urban estimates (after adjustment) were roughly comparable with the CBO’s, while RAND projected a much smaller reduction in the number of uninsured, based on an assumption of much slower phase-in of Medicaid coverage.

In 2015, the CBO estimated that the ACA’s insurance expansions had reduced the number of uninsured by 12 million, from a (slightly lower) baseline of 54 million to 42 million. 10 The CBO’s 2015 estimate of the reduction in the uninsured population was about 86 percent as great as the CBO’s 2012 estimate of 14 million, but the remaining uninsured population matches the CBO figure nearly exactly. This apparent anomaly occurred because slower health care cost growth meant that there were fewer uninsured in the baseline (no-ACA) world than the CBO had originally expected (a difference of 2 million people). The latest estimate from the National Health Interview Survey, which uses a somewhat different metric from the CBO’s, suggests that about 36 million people remain without health insurance. 11

Health care cost growth between 2010 and 2014 was much slower than any of the estimators had anticipated. Moreover, competition in marketplaces, combined with ACA mechanisms to reduce risk, appear to have kept premium increases associated with the ACA itself in check. The 2014 benchmark premium (the average premium for the second lowest-cost silver plan) averaged $3,800, 12 about $900 below the CBO’s estimate (Exhibit 3).

| Source and date of projection | CBO August 2010 a | CMS 2010 b | RAND 2010 c | Lewin 2010—adjusted d | Urban Institute 2010—adjusted e | Realized 2014 f |

| Average subsidy per subsidized enrollee | $3,817 | $4,366 | $4,651 | $4,362 | $3,341 | $4,425 |

| Benchmark premium | $4,700 g | — | — | — | $4,618 h | $3,800 |

a Congressional Budget Office (August 2010). Health Insurance Exchange Projections, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/dataandtechnicalinformation/ExchangesAugust2010FactSheet.pdf. We estimated the CBO fiscal year average subsidies on the assumption that 2014 fiscal year average enrollment would be three-fourth of calendar year enrollment.

b Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (April 2010), Estimated Financial Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act as Amended: Table 1, http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/downloads/PPACA_2010-04-22.pdf.

c RAND (2010). Analysis of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (H.R. 3590): Table 1, http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_briefs/2010/RAND_RB9514.pdf.

d Lewin estimates assume full implementation of the Act. Lewin (June 2010). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA): Long Term Costs for Governments, Employers, Families and Providers: Figure 9. Calculated by dividing total subsidy payments by number of subsidized enrollees, http://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/LewinGroupAnalysis-PatientProtectionandAffordableCareAct2010.pdf.

f Congressional Budget Office (April 2014). Updated Estimates of the Effects of the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/45231-ACA_Estimates.pdf.

g Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (August 2013). Market Competition Works: Silver Premiums in the 2014 Individual Market Are Substantially Lower than Expected, http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2013/MarketCompetitionPremiums/ib_premiums_update.pdf.

h Urban Institute estimates assume full implementation. Urban Institute (December 2010). Why the Individual Mandate Matters: Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412280-Why-the-Individual-Mandate-Matters.PDF. Urban estimates are adjusted to 2014 premiums by multiplying all figures upward by 12.5%, assuming projected 2010–2014 premium increases of 3% per year, consistent with the 2007–2010 period.

The sharp reduction in the premium for the benchmark plan had very little effect on the average subsidy amount per subsidized enrollee though it did affect the number of people eligible for subsidies, as discussed below. The smaller number of people receiving subsidies (both because of lower eligibility and lower enrollment) reduced total expenditures for marketplace subsidies relative to the estimate 13 to $15 billion, about 79 percent of the original CBO projection (Exhibit 4).

| Source and date of projection | CBO August 2010 Baseline a | CMS 2010 b | RAND 2010 c | Lewin 2010 d | Urban Institute 2010 e | Realized 2014 f |

| Premium credits (fiscal year) | $16 | $38 | $38 | — | $14 | $11 |

| Cost-sharing reductions outlays (fiscal year) | $3 | $6 | $2 | — | $3 | $2 |

| APTC+CSR outlays (fiscal year) | $19 | $44 | $40 | $35 | $17 | $15 |

Note: The CBO reported figures for total outlays include related spending of $1 billion for marketplace grants. We subtract this figure from the CBO forecasts and realized estimates.

b Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (April 2010), Estimated Financial Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act as Amended: Table 1, http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/downloads/PPACA_2010-04-22.pdf.

c RAND (2010). Analysis of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (H.R. 3590): Table 1, http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR100/RR189/RAND_RR189.pdf. We assume the fiscal year estimate for RAND is three-quarters of the calendar year estimate. We compute the share receiving premium subsidies in 2014 based on the projection in this report that premium subsidies would account for 96% of subsidy expenditures by 2019.

d Lewin (June 2010). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA): Long Term Costs for Governments, Employers, Families and Providers: Figure 9. Lewin reports total figures for 2014; we calculate subsidies per subsidized person by dividing this figure by our adjusted enrollment estimate. http://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/LewinGroupAnalysis-PatientProtectionandAffordableCareAct2010.pdf.

e Urban Institute, (December 2010). America Under the Affordable Care Act: Table 2, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412267-America-Under-the-Affordable-Care-Act.PDF. We adjust the Urban figures for health care cost inflation between 2010 and 2014 (12.5%) and for the phase-in of coverage, using the CBO’s phase-in estimate.

f Congressional Budget Office, Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act— CBO’s April 2014 Baseline, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/51298-2014-04-ACA.pdf.

We examined the accuracy of the CBO’s model by mimicking how accurately it would have predicted actual marketplace enrollment if the CBO had known the income levels, insurance coverage rates, and premium rates that existed in 2014 (see Appendix Exhibit B1). The much lower than anticipated benchmark premiums reduced the number of people who might have been expected to qualify for any subsidy by more than 2 million people (about 7%). Differences in the distribution of income reduced the number of people who might have qualified by about 1 million (about 3%). After applying the actual income levels, insurance coverage rates, and benchmark premiums, we conclude that the CBO model’s prediction would have been just over 6 million subsidized enrollees. Actual marketplace enrollment in 2014—5 million—is about 18 percent below this revised forecast. This difference is, in part, attributable to the slower-than-expected rollout of the marketplaces.

There have been very few efforts to gauge the accuracy of models that project the effects of health reforms. 14 In an earlier review, the CBO’s estimates were usually found to fall within 30 percent above or below actual experience, as they did here. 15 In the case of the ACA, about half of the CBO’s prediction error was because of its forecast of what conditions in 2014 would be before taking into account the effects of the ACA. The CBO had projected that health care prices would be much higher and that incomes would be lower than what turned out to be the case. After adjusting for these differences in baseline assumptions, the CBO estimate came within 18 percent of actual experience.

Simulations of the effects of health insurance reforms have received considerable attention over the past two decades, leading to substantial improvements in modeling. The CBO, and several private forecasters, were fairly accurate in their predictions of the likely coverage and cost implications of the ACA. A few forecasters—notably the CMS—assumed much higher rates of responsiveness to subsidies and coverage expansions, and these models generated the least accurate predictions. CMS estimates of participation in subsidized coverage, Medicaid enrollment, and total marketplace spending were 2.7, 2.0, and 2.9 times, respectively, higher than actual figures.

The Affordable Care Act was a critical step in expanding health insurance coverage, but it is unlikely to be the last national health policy reform considered by Congress. It is therefore reassuring that despite many factors that could not have been foreseen in 2010—such as the ACA’s troubled rollout and the lack of state support—the CBO model proved to be reasonably accurate compared with actual experience and the estimates of other modelers. This should allay concerns of some critics that its forecasts were biased in favor of the Administration.

a Take-up rates from Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (March 2012). Understanding Participation Rates in Medicaid: Implications for the Affordable Care Act, http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2012/medicaidtakeup/ib.shtml.

Since we do not have access to the CBO model, we use information from published documentation to assess how the CBO related marketplace insurance subsidy levels to projected participation rates by income.

We estimate the difference between the CBO’s 2014 predicted marketplace premiums—using their 2010 forecast and actual premiums in 2014, as well as the 2009 distribution of income and coverage—compared with the actual income distribution in 2013. We compare subsidy participation by relating the subsidy levels to nonsubsidized benchmark premiums. We use information from the CBO’s methodology description to estimate subsidized take-up rates. 16 This comparison yields an estimate of the baseline participation rates associated with varying subsidy percentages in the CBO model.

Our baseline participation estimates modeled in this way are not directly comparable to the CBO’s 2010 estimates. Many features of the CBO’s model are not described in their published methodology, and some parameter assumptions may have changed subsequent to publication of the methodology report. We do not know their baseline assumptions about incomes, coverage, or premiums, and we make no adjustment for citizenship or residency. Most important, to estimate the effects of the ACA, the agency used an estimate of what nongroup premiums would be in the absence of the ACA in calculating participation. By contrast, in our simulation we assume that nongroup market premiums without reform would be equal to benchmark plan premiums. Benchmark plan premiums, however, incorporate all ACA changes, including benefit plans, rating changes, and loss ratios. To address these various differences, we calibrate our baseline participation estimates to match the published CBO estimate of 7.1 million subsidized enrollees in 2014. That is, we generate take-up rates for income/subsidy cells based on published information and further adjust them to generate the 7.1 million estimate.

We then repeat our estimates, and use the same calibration adjustment, to project how much enrollment forecasts would have varied if premiums, income levels, and coverage distributions were known.

We first use the projected premium price of $3,100 for a 21-year-old male—derived from the $4,700 average benchmark premium that the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) infers based on the CBO’s 2010 report—to estimate enrollment. We then estimate enrollment with the actual premium price of $2,508 for a 21-year-old male (derived from the $3,800 premium reported in the CBO’s April 2014 report 17 ). We assign age-rating factors to benchmark premiums using the Rating Factor Limitations report by Coventry Health Care and an ASPE report on premiums released June 18 2014. 18 Data from the Current Population Survey for survey years 2009 and 2012 were used to construct the share of individuals under age 65 who would qualify for any subsidy and to predict enrollment under forecast and actual conditions.

The CPS measure of insurance coverage changed in 2014. To avoid this problem, we next applied the simulated take-up rates to data on the distribution of uninsured individuals and individuals with individual insurance plans under age 65 by household income from the American Community Survey one-year estimates, 2009 and 2013, available on American FactFinder.

(all figures in thousands)

| 2010 | 2014 | Difference as a result of income change (holding premium constant) | ||||||

| Uninsured and nongroup population 100%–400% FPL | Population qualifying for any subsidy | Population predicted to take up subsidy | Uninsured and nongroup population 100%–400% FPL | Population qualifying for any subsidy | Population predicted to take up subsidy | Population qualifying for any subsidy | Population predicted to take up subsidy | |

| Forecast benchmark premium | 38,738 | 34,506 | 7,100 | 36,917 | 33,175 | 7,008 | –1,331 | –92 |

| Realized benchmark premium | 38,738 | 32,147 | 6,122 | 36,917 | 31,126 | 6,069 | –1,022 | –53 |

| Difference as a result of premium change (holding income constant) | –2,359 | –978 | –2,049 | –938 | ||||

| Combined effect | 3,380 | 1,031 |

1 CBO concluded that only 70 percent as many people would gain eligibility for Medicaid as had previously been assumed and that some people with incomes between 100 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty level residing in states that would not expand Medicaid would obtain insurance offered through the marketplaces. It also assumed that greater take-up of marketplace subsidies among this lower-income, sicker group would lead to a higher average subsidy for enrollees.

2 Under the ACA, premium subsidies are available for purchases in the marketplaces only, but unsubsidized enrollees could obtain coverage outside the marketplace. While modelers differed in their assumptions about how many unsubsidized enrollees would choose off-marketplace enrollment, we do not have estimates of the actual off-marketplace enrollment with which to make comparisons.

3 R. S. Foster, Estimated Financial Effects of the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” as Amended (Darby, Pa.: Diane Publishing Company, 2010).

4 RAND COMPARE, Analysis of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (H.R. 3590) (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND, 2010), http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_briefs/2010/RAND_RB9514.pdf.

5 Lewin estimates assume full implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Lewin Group, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA): Long Term Costs for Governments, Employers, Families and Providers (Falls Church, Va.: Lewin Group, June 8, 2010), Figure 9, http://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/LewinGroupAnalysis-PatientProtectionandAffordableCareAct2010.pdf.

6 M. Buettgens, B. Garrett, and J. Holahan, America Under the Affordable Care Act (Princeton, N.J., and Washington, D.C.: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute, Dec. 2010), http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2010/12/america-under-the-affordable-care-act.html.

7 Lewin Group, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA): Long Term Costs for Governments, Employers, Families and Providers (Falls Church, Va.: Lewin Group, June 8, 2010), Figure 9, http://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/LewinGroupAnalysis-PatientProtectionandAffordableCareAct2010.pdf.

8 Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2015 to 2025 (Washington, D.C.: CBO, Jan. 2015), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/49892.

9 Congressional Budget Office, H.R. 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Final Health Care Legislation) Cost Estimate (Washington, D.C.: CBO, March 2010), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/21351.

10 Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2015 to 2025 (Washington, D.C.: CBO, Jan. 2015), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/49892.

11 R. A. Cohen and M. E. Martinez, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2014 (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health Interview Statistics, June 2015), http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201506.pdf.

12 Congressional Budget Office, Updated Estimates of the Effects of the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act (Washington, D.C.: CBO, April 2014), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/45231.

13 Total marketplace subsidies include premium credit outlays, reductions in revenues from premium credits, and outlays for cost-sharing subsidies.

14 The CBO recently presented findings comparing its original marketplace enrollment projections with those realized. J. Banthin, “Forecasting Enrollment and Subsidies in the ACA Exchanges,” Roundtable presentation for the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, Miami, Fla., Nov. 14, 2015, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/presentation/51003-acaexchanges.pdf.

15 S. Glied and N. Tilipman, “Simulation Modeling of Health Care Policy,” Annual Review of Public Health, 2010 31:439–55.